Medieval

Our story begins with a miracle, when the waters of the River Lea parted in the manner of the Red Sea, allowing the wondrous passage of the body of St Erkenwald, carried across the dry riverbed on his journey from Barking Abbey to his final resting place in St Paul’s Cathedral in 693. Legend has it that when the saint’s body was laid down in Bow upon what became the site of the church, flowers blossomed where the bier sat upon the ground.

Our history continues with an accident, when Queen Matilda fell into the River Lea on her way to Barking in 1110 and became ‘well wetted with water,’ according to medieval historian John Leland. In the absence of miracles and to avoid future muddy mishaps, Matilda ordered the building of a bridge at this spot. Leland tells us it was ‘arched like unto a bowe,’ which gave the name to the village that grew up beside the crossing where a community of bridge keepers, boatmen, millers, fishermen, farmers, bakers, butchers, fullers, saddlers, dyers and cap makers flourished.

Each winter the inhabitants of Bow grew sick of trudging through the muddy paths to the parish church of St Dunstan’s in Stepney and launched a petition, believing that they were worthy of having their own place of worship, inspired perhaps by the building of the White Chapel in Aldgate. On 7th November 1311 Bishop Baldock of London complied, licensing the construction of a ‘chapel of ease’ at Bow and in 1327 King Edward III granted a piece of land ‘in the middle of the King’s Highway,’ where the chapel was founded as daughter church to St Dunstan’s.

Shrine of St Erkenwald at St Paul’s by Hollar

Portrait of Queen Matilda

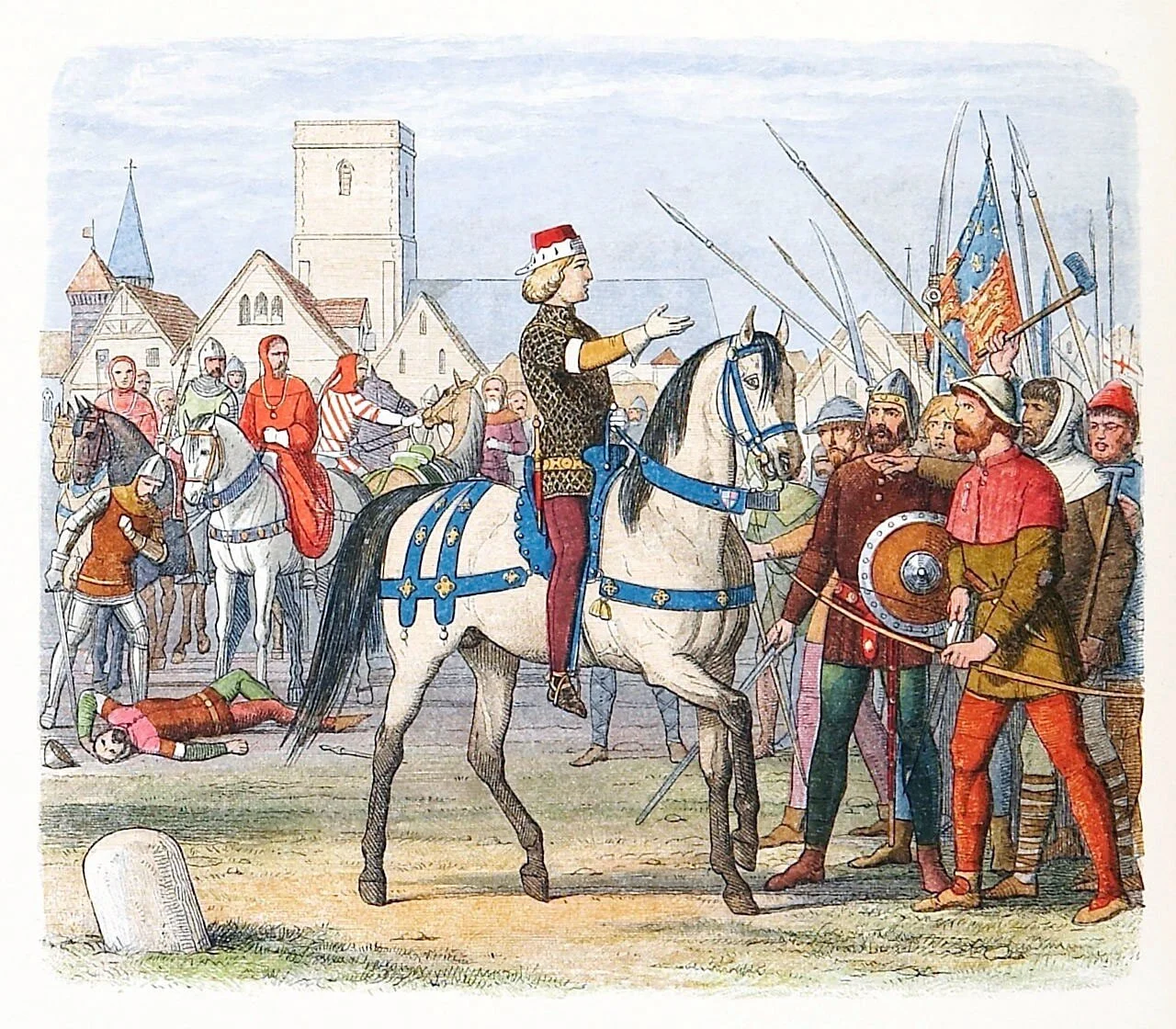

Picture of the Peasants’ Revolt

A few years later in 1348 the Black Death pandemic arrived, blighting the land and killing as many as half the population which led to a labour shortage and the expectation of higher incomes. But the Statue of Labour of 1351 capped wages, escalating grievances and social unrest that contributed to the Peasants’ Revolt of 1381 in which over 1,500 people died.

Demanding an end to serfdom, protestors led by Wat Tyler marched from Essex through Bow in May to confront the fourteen year old King Richard II on Stepney Green. Although he acceded to their wishes, they entered London in June, sacking the Savoy Palace and occupying the Tower of London. Richard met with the rebels again in Smithfield where violence broke out and Wat Tyler was stabbed by William Walworth, Mayor of London, crushing the revolt.

The growth of the community at Bow over the next century was such that the chapel of ease acquired its first priest in 1456, recorded simply as ‘John.’ Significant legacies from local tradesmen permitted the improvement of the building, known as ‘The Great Work,’ enlarging it to the size it is today by 1490. John of York, a baker, left £13 4d to pay for candles and £3 towards the building of a steeple. John Laylond, a carpenter, bequeathed his stock of timber for ‘making doorways and floors of the new belfry.’ Richard Robyn, chapel warden, left forty shillings for the steeple and John Bruggis left £3 for glazing the west window.

The octagonal font from 1410

At this time, a vaulted crypt of sixty feet long was constructed beneath the nave to store the bodies of parishioners until Judgement Day, which was sealed by government health order in 1891. The lower part of our tower of Kentish ragstone dates from this era, as does the battered octagonal font that was was discarded in 1624 in favour of a more modern design. After three hundred years as a garden ornament, it was rescued and continues in use for baptisms.

Plan of original structure and enlargement of the church

The lower part of the tower dating from the fifteenth century

As more houses, shops and taverns were built surrounding the churchyard, it created a public space for gatherings and markets, especially at public holidays and seasonal festivals. Thus arose the celebrated Bow Fair, recalled today in the street name of Fairfield Road. The market had its origins as a Green Goose Fair held at Whitsuntide for the sale of young geese from the surrounding countryside.

Every Whit Wednesday, the congregation of Bow visited their mother church of St Dunstan’s, walking in procession through the fields to pay their dues of twenty-four shillings, declaring their membership of Stepney parish and participating in a service of worship. Bow Fair culminated an annual week of festivity in summer. Over proceeding centuries, the fair attracted large crowds of visitors from London and Essex, acquiring a reputation for debauchery and drunkenness, as Shakespeare’s contemporary Gervase Markham wrote in 1600.

“‘To Stratford Bow unto the Greengoose Fair

A world of people one day did repair

Both poor and rich, men likewise old and young.

Mixt with the males, the females came along.

The season of the year as usually was parching hot,

The weather scorching dry.

Hay makers, mowers, thither did repair.

Compelled by the sultry-hot-fire breathing air

The extreme heat did cause a thirst

So they drank until they almost burst.’”