Victorians

Of nineteenth century Rectors, Samuel Henshall who came to Bow in 1802 from Christ Church, Spitalfields, is perhaps the best remembered, for his patenting of the first improved corkscrew. His improvement which consisted of a button on the shank of a corkscrew to improve grip was actually someone else’s idea but, by registering the patent, he took the credit. It did him no good because he died in debt in 1807 and is buried in the sanctuary, accompanied - reputedly - by all his unsold corkscrews.

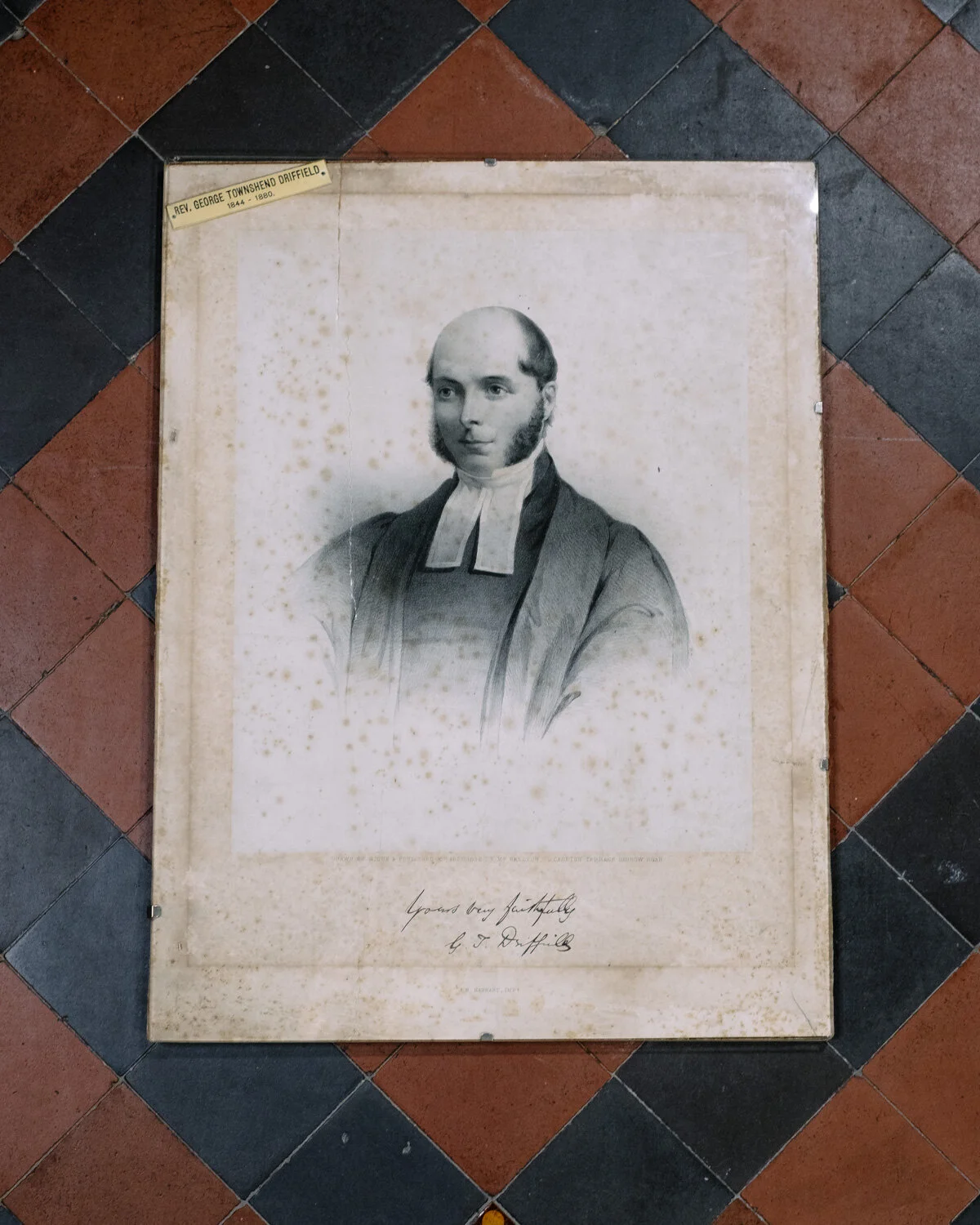

Portrait of George Driffield

Yet it was George Driffield, Rector from 1844 until 1880 who made the greatest mark upon the parish, overseeing the transformation of Bow, as the small village was swallowed up by the monstrous sprawling wonder of Victorian London, with overcrowding, poverty, pollution and disease.

The Match Girls

The abolition of Bow Fair in 1823 signalled the passing of a rural society, as suburban sensibilities accompanied the development of new terraces in Fairfield Road and across the parish. Margaretta Brown left a bequest for the religious education of local youth and school prizes in 1826, insisting ‘no rewards are to be given to any boys who should beg for bonfires and throw squibs and crackers, by which persons are frequently injured and sometimes killed by their horses taking fright!’

An Act of Parliament of 1824 permitted the compulsory purchase and demolition of the old buildings which surrounded the church, creating the open churchyard we see today. After part of the tower collapsed in a storm in 1828 it was ‘restored’ in a nineteenth century medieval style with battlements added and the ancient Bow bridge was replaced by a new granite structure in 1839. The Eastern Counties Railway opened the same year, steaming through the parish, and a regular bus service began from Bow to Hyde Park via Oxford Street which is still running today.

But while these improvements in urban infrastructure were happening, the church had to distribute coal, potatoes and bread to seven hundred families who were struggling to survive the cold winter of 1838. London’s last great cholera epidemic broke out close to the church in 1866, caused by poor housing conditions and contaminated water. Such was the paradox of economic disparity in George Driffield’s parish. Migration within Britain and from beyond was to increase the population of Bow from 2,000 in 1800 to 42,000 in 1900. The large numbers of Irish migrants escaping the potato famines in their own country led to parts of Bow being labelled ‘Fenian Barracks.’

The Bryant & May Match Factory opened in 1861, offering employment to large numbers of local women, many of whom were Irish, in poor and exploitative conditions. The exposure to phosphorus in the manufacturing process caused a cancer that ate away their faces, known as ‘phossy jaw.’ A group of brave women who became celebrated as the ‘Match Girls’ led a successful strike in protest at their suffering, winning better conditions and pay through creation of the first trade union.

With evangelical zeal, George Driffield joined the local Board of Guardians, working to ameliorate poverty in his parish, and founded three new churches for the growing population - St Stephens North Bow in 1857, St Mark’s Victoria Park in 1873 and St Paul’s Old Ford in 1878. He removed Priscilla Coborn’s plaster ceiling from his own church, halted burials in the overcrowded churchyard and modernised services, putting in a new organ and forming a choir. In the pursuit of better housing for the poor, he became a property developer, directly involved in the construction of the Bloomfields Estate in Bethnal Green.

Surrounded on all sides by modern redevelopment, the old church appeared more and more of an anachronism in the nineteenth century. Walter Besant described it in his novel ‘All Sorts & Conditions Of Men’ in 1882, ‘the beautiful old church of Bow, standing in the middle of the road, crumbling slowly away in the East End fog, with its narrow strip of crowded churchyard. One hopes before it has quite crumbled away someone will go and make an etching of it.’

Although repair work was done in 1891, it did not prevent the chancel roof from collapsing in 1896 which caused the East London Advertiser to publish the headline, ‘Bow Church Is Doomed.’ It was proposed that only the tower be retained with the churchyard turned over to become a public park and even the chairman of the vestry concluded that ‘the demolition of the church would entirely raise the tone of Bow Road.’

Fortunately there were those who disagreed, including CR Ashbee of the Guild of Handicrafts in Mile End. The Guild was a workers’ co-operative of craftsmen organised upon the ideals of William Morris. Backed by the Society for the Protection of Ancient Buildings, which had been founded by Morris in 1877, a committee was formed to organise the repairs and a temporary corrugated iron church constructed in front of the west door.

Following Morris’ principle of repair over restoration, the chancel roof was rebuilt using the old timbers and large plain oak beams inserted across the nave to hold the exterior walls in place which had been leaning outwards in danger of collapse. Iron clad cart wheels clattering over stone cobbles on either side created so much noise as to make the church almost unusable until Ashbee had the inspired idea to fit secondary glazing, which still survives as the earliest example of double glazing in a church.